Earliest New Zealand Gardens

Although my ODH project is focused on the influence of the British on New Zealand garden design, the current trend towards integrating native plants and indigenous cultural traditions must be placed in the context of the pre-European history of New Zealand.

Helen Leach's 1984 book 1,000 years of Gardening in New Zealand details the history of vegetable growing in New Zealand by the Polynesian immigrants who later became the Maori people. This study of domestic horticulture (in the garden) is in contrast to studies of agriculture (in the field) , and focuses on what individuals and families were able to grow using simple tools such as digging sticks and hoes, as opposed to ploughs. This focus also means that Leach investigates plants that were grown individually, often by means other than seed (cuttings, slips, bulbs, or rhizomes) . This history of raising plants specifically for gardens is a strong characteristic of New Zealand's horticultural inheritance.

Leach cites evidence that the Austronesians (from whom the Polynesians descended), who colonized Melanesia from about 4,000 BC, were already horticulturists (as opposed to gatherers) and brought with them the means and knowledge to cultivate roots crops such as taro and yam, and other crops such as breadfruit and banana.

Through archaeological and comparative anthropological evidence, Leach paints a picture of the Maoris, by the time of European arrival in the late 1700's, as highly sophisticated horticulturists capable of cultivation and storage of a wide variety of food plants. The ancestors of these people had had to adapt their tropical gardening practices to New Zealand's temperate climate, and had obviously done so admirably. For example, "methods of laying out land and of marking boundaries with walls, fences, and ditches...along with the knowledge of the value of mounds for growing yams, gourds and, later, sweet potatoes, and of the benefits of basin-like depressions for growing non-irrigated taro...stone faced terracing for holding back soils on steep slopes, and mulching with grass to retard evaporation" (p. 32): all of these were techniques the Polynesians brought and adapted to New Zealand's climate and terrain.

The earliest settlers in New Zealand found a place quite different from their homeland, but Leach points out that the Marquesas Islands (agreed as a likely starting place for Polynesian emigrants to New Zealand) share 28 of their 113 genera of plants with New Zealand. Thus, the first settlers would have found quite a number of familiar plants, which explains why the Polynesian and Maori words for many plants are very similar. Leach notes that "the first Polynesian settlers probably felt more at home in New Zealand than the first Europeans, who, beacuse of the unfamiliarity of their environment, abandoned many of their initial names for plants...in favour of Maori names. So today we use rimu instead of red pine, manuka instead of tea-tree..." (p. 54).

The detailed history of these early Polynesian settlers, up to the time of the arrival of the Europeans, is beyond the scope of this project, but it is worth noting that many of the plants often taken as indigenous to New Zealand were in fact introduced by the Polynesians, and that their cultural practices interacted with naturally occuring climatic conditions (similar to the changes associated with Europe's 'little ice age' from 1600-1850 A.D.) to alter the landscape they originally found. Specifically, early coastal gardens exposed vulnerable soils , which then eroded and changed water conditions, and, eventually, the shellfish, fish, and bird populations. As always, "many human actions make the land more vulnerable to natural catastrophes than it would otherwise be" (Leach, p. 63).

Leach tells the story of the probable trials and struggle the Polynesian settlers faced as they struggled to adapt to New Zealand conditions, and concludes that "with the help of some sound horticultural techniques such as soil-lightening, mulching, wind-break screens, and raised planting beds, coupled with ingenious storage devices and a great deal of faith, Maori gardeners of the pre-European period turned potential disasters into qualified success " (p. 72).

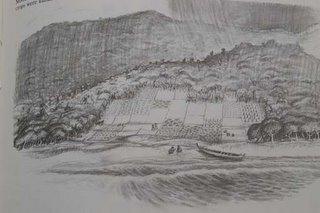

By the time Captain Cook arrived at Anaura Bay in the late 18th century, he observed and recorded horticultural practices that would have looked quite familiar to him. Maori gardens were rectangular, fenced by woven reed panels, and subdivided into further rectangles for various plants. Gardeners used digging sticks with crosspieces for a footrest attached, like a simple spade, and other very familiar-looking tools. Cook described "a piece of wood fashioned a bit like a trowel...also a piece of wood in the shape of a mattock of two or three feet in length" (p. 66). From this time onwards, the gardens of New Zealand were open to the influence of European plants, tools, and cultural traditions. (illustrations below by Nancy Tichborne, in Leach, pp. 65 and 69)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home