The legacy of 19th c. New Zealand kitchen gardens

It is quite remarkable how quickly the Europeans created very English gardens in New Zealand. Helen Leach, in her book 1,000 years of gardening in New Zealand (1984), describes the rapid establishment of English style kitchen gardens in New Zealand. Early settlers made gardens "with an eye to provisioning later visitors" (Leach, 1984, p. 110) and by the time the missionaries arrived and began writing regular reports of conditions, a number of gardens were already established.

The missions themselves were among the largest early European-style kitchen gardens in New Zealand. The mission at Kerikeri, established by 1819, included "a hundred grape vines, 100 fruit trees, and 85 other garden trees" (p. 111). The kitchen garden plant list for 1821-22 included hops, turnips, carrots, radishes, cabbages, potatoes, lettuce, red beet, broccoli, endive, asparagus, cresses, onions, shallots, celery, rockmelons [cantaloupe] and watermelons, pumpkins, cucumbers, parsley, grapes, strawberries, raspberries, oranges, lemons, apples, pears, peaches, apricots, quinces, plums and almonds. As well, herbs included peppermint and spearmint, sage, lavender, rosemary, and rue plus the flowers marigolds, lilies, roses, pinks, and sweet william. These lists are astonishingly diverse and completely English, including all the usual kitchen garden vegetables (wheat, oats, barley, peas and beans were grown as field crops both in England and in New Zealand by this time) as well as those grown under glass in Europe. Notably, the two most important Maori crops, maize and sweet potatoes, are not listed, either because they traded for these with the natives, or because they were not yet eating these unfamiliar vegetables.

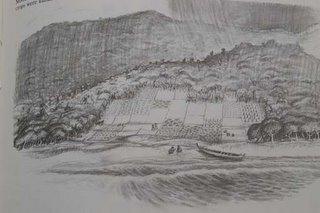

However, clearly the missionaries wasted no time in taking advantage of the milder and longer growing season to recreate their preferred diet. By the time the famous evolutionist Charles Darwin passed by New Zealand in 1835, he was comforted in his homesickness by the sight of "the English flowers in the platforms before the houses; there were roses of several kinds, honeysuckle, jasmine, stocks, and whole hedges of sweet brier" (in Leach, p. 112). Darwin also noted "there were large gardens, with every fruit and vegetable which England produces" and called the farmstead "a fragment of Old England" (in Leach, p. 113). The photo below (in Leach, p. 115) shows a Te Awaiti garden in the late 19th c., and includes a "garden path lined with hollyhocks, sweet william, delphiniums, antirrhinums, and roses, the area in the foreground was planted with neat lines of gooseberry bushes...beyond them cabbages grow beneath a peach tree."

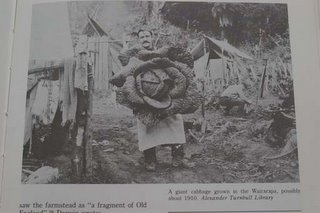

Indeed, gardeners in New Zealand could boast of results far exceeding those of their cousins in England, due to New Zealand's climate and the fertility of the virgin land. Enormous vegetables were recorded in various mission stations: turnips of 80 centimeters girth, cabbages of 104 centimeters in diameter, weighing 6.8 kilograms! With such results, it didn't take long for the homesteaders to form a Horticultural and Botanical Society to sponsor an annual show at which to show off their results. The first exhibition was held in Wellington in 1842--at that show, a cabbage weighing 9.7 kilograms was exhibited! (Photo from 1910 exhibit below from Leach, p. 113)

Word of this bounty filtered back to England, and many professional nurserymen were among the early settlers, establishing flourishing and profitable nurseries to respond to the new settlers' hunger for European plants. For example, William Hale of Nelson raised .8 hectares of onions, .4 hectares of rhubarb, thousands of cauliflower and cabbage plants, and 10,000 fruit and forest trees for sale, within five years of his arrival. Other settlers brought sufficient gardening knowledge to slowly establish their own homesteads by working first as gardeners for established settlers. One such settler was George Jupp, of New Plymouth, whose (1828-1919) diary is an unusually detailed record of life in New Zealand at the time. Within a month of his arrival, George had earned enough by working at established properties to start his own garden, and within a year was well enough established to be nearly self-sufficient.

This paradise was soon, however, to be infected by the evils brought along with the gifts. Weeds were imported along with the desirable plants. Dock, which may have been fraudulently sold in place of tobacco seed, soon infested the entire country--in fact, a dock plant was the first to surface through an 11 c. blanket of ash after the 1886 eruption of the Tarewara volcano! Gorse, imported to be used as a hedging plant as in England, soon infested even the high country, and its prickly impenetrability continues to be a problem even today. Oxalis also took over the landcape, and the hawkweeds (Hieracium pilosella, prealtum, lepidulum, caespitosum), introduced in contaminated seed over 100 years' ago, still spread their ground-blanketing foliage over hectares of land, their low growth habit crowding out valuable grazing plants and reducing land values (Spirit of the High Country: the search for wise land use, The South Island High Country Committee of Federated Farmers, 1992). Research is ongoing into control measures for these invasive exotics.

Even the English flowers naturalized. Just as the Canadian roadsides are now so covered with daisies, mullein, and Queen-Anne's lace that we almost think of these as Canadian wildflowers, Russel hybrid lupins are now a pretty but persistent pest along high country waterways in New Zealand's South island.

There is much debate in current rural circles in New Zealand about the preservation of the country landscape, but the question is asked: what landscape is worthy of preservation (pre-Polynesian, pre-European, or current)? Sheila Egoz, a senior lecturer in landscape architecture at Lincoln University in Christchurch, points out that thoughtless development (urban sprawl) is destroying a rural landscape that has both cultural and tourist value for New Zealanders. Dr. Egoz points out that the "the Resource Management Act has provisions for the protection of 'outstanding landscapes' but does not offer protection for the everday ordinary farming landscape that embodies important heritage values to New Zealand society" (Outlook, Lincoln University, Dec 2005, p. 30). Far from suggesting that development should halt, however, Dr. Egoz is calling for a think tank of relevant parties, including landscape architects, soil scientists, environmental scientists, property and valuation experts, sociologists, geographers, horticultural and and agricultural scientists, and farm and horticultural management personnel. Dr. Egoz has recently studied other models of sustainable development in Portugal and Switzerland that she suggests are worth emulating in New Zealand.

By the middle 1800's, fruit trees were dying from infestations of diseases and pests brought in by European settlers, either intentionally or inadvertantly. The Polynesians brought the Sphinx moth, whose larvae attacked the Maori kumara (a type of yam); Europeans brought in the first slugs and snails on their ships. Today, biosecurity measures in New Zealand are a major focus, to prevent further infestations. At Lincoln University, Dr. Karen Armstrong and Dr. Sue Worner, of the National Centre for Advanced Bioprotection Technologies, continue to seek new and better ways of predicting the invasive potential of new insect species in order to target containment and eradication efforts. Dr. Worner is using state-of-the-art GIS technologies to map the extent of existing pests such as the Asian gypsy moth and Argentine ants. Dr. Armstrong, working with a Canadian Dr. Shelley Ball (formerly of the University of Guelph), is establishing DNA barcodes as part of an international database project (the Barcoding of Life project), to assist border efforts in identifying and eradicating potential invasives. As the article in Lincoln University's Outlook (Dec 2005) magazine states, "more than anywhere else, New Zealand must pay close attention to biosecurity, since 80 million years of geographical isolation has resulted in ecosystems that are highly susceptible to invasive species" (p. 5).