Emily's Garden

Emily’s Garden: The Colonial New Zealand Garden of a Suffolk Lady, edited and illustrated by Kerry Carman; Random Century NZ Ltd. 1990

This book is a new edition of a book originally published in 1902 in New Zealand, by an English immigrant lady by the name of Emily Marshall-White, the “Suffolk Lady” of the title. It is the chronicle of the various gardens created in the colony by this lady and her daughter Jessie over a period of 25 years (between 1876 and 1901). The text, sprinkled with Emily’s many religious references, makes for fascinating reading. Her tales reveal that the members of New Zealand society in its pioneer days struggled to create an environment as close as possible to upper class England, despite having to cope with rather more hands-on contact with the elements than they had been accustomed to.

Emily and John Marshall moved to NZ in 1876, leaving behind substantial family lands and wealth, in an attempt to cure John of his illnesses through the warmer climate and fresher air of NZ. In the midst of the traumas inherent in hacking out a homestead in a new and untried environment, with a husband whose continuing ill health made him almost an invalid, Emily successfully raised five children and quickly established a successful garden at her first home site. Although “the Suffolk Lady, like many other aristocratic English women before her, expected to be able to hire a full complement of servants on her arrival—great must have been her dismay to discover she would be obliged to manage alone” (17). The family’s plight was alleviated by a neighbouring pioneer, a Mr. Blanco White, who assisted them so much that, when Emily’s husband died several years later, she eventually married Mr. White.

Emily’s first NZ garden was in Nelson, in the north of the South Island, and the warm climate and fertile soil soon rewarded her efforts. A photo taken only two years on shows a thriving passionfruit vine against the house and abundant growth in the surrounding vegetable and fruit gardens, critical to maintaining her family's health (Carman 18).

After her husband’s death in 1879, Emily took her children back to England where they could be properly educated to prepare them to someday take up the lands they were heir to in England through her own and their father’s families. However, she returned to NZ in 1882 after marrying Mr. White in 1881. Kerry Carmen reports that Emily “found it difficult to settle back into the English lifestyle after becoming so self-sufficient in New Zealand" (20). Upon her return, the family settled on the North Island, at Grove House in Wanganui, and Emily soon established another lush English-style garden, including courts laid out for the family's passions, croquet and tennis. However, Emily's new garden also incorporated a full range of both exotic and NZ native plants as she became more knowledgeable through her participation in the local Horticultural Society. Emily imported exotic tree and shrub seeds from all over the world via the many thriving mail-order nurseries of the day, and not only had success in raising plants from the seed for her own garden, but became something of a distributor of certain species such as the scarlet-flowering gum from Australia. (Carman 22)

Photos of Emily working in her Wanganui garden show her attired as a proper English Victorian lady in long skirt and wide-brimmed hat, but the garden boasts twenty-year-old cabbage trees (or 'palm lilies' as Emily knew them), blooming lilium giganteum, and a flourishing paulownia. She writes of 'ferning' expeditions into the native bush, and one photo shows several huge 'ferns' (actually palms, I believe) being brought home with the aid of a cart and horse. Emily had great success transplanting these large specimens, but wrote scathing comments on those who "denuded the bush to decorate ballrooms with fern fronds and whole nikau palms" (Carman 28).

These gardens were to last longer than her second marriage, which ended after three years when Mr. White became frustrated with his inability to access Emily's familial wealth, due to the new Married Women's Property Act of 1882.

These gardens were to last longer than her second marriage, which ended after three years when Mr. White became frustrated with his inability to access Emily's familial wealth, due to the new Married Women's Property Act of 1882.

Emily's flowers constantly won awards at the local shows, and her success with chrysanthemums may have spurred her founding of the local Chrysanthemum Society. Her garden style was, for all its exotic additions, still very English, with a forecourt laid out in a formal parterre, and straight-edged beds for her many floral gems. Her violets and other tussie-mussie flowers were so abundant that she and her daughter used to sell posies to travellers at the local train station, as a fund-raising venture for the Horticultural Society.

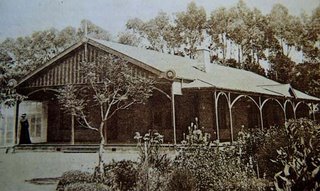

Her large Wanganui garden was eventually subdivided and she limited her efforts to a smaller but still lush garden around a newly-built, smaller house named 'The Bungalow'. (Carman 35)

As her children grew and inherited estates in England, and following the death of one of her sons, Emily returned to England for a brief time, and while there published the first edition of her little book by 'a Suffolk lady,' but eventually re-established herself in NZ at Greenbank, her son George's house near Marton, a few hours north of Wellington on the North Island. After George's marriage, she and her daughter Jessie moved to nearby Marton Junction and Emily began again with a new garden, named 'Elmswell' as a play on her initials (Emily Louise Marshall) and as a celebration of the return of her good health after some years of decline following her son's death.

Emily continued to be active in horticultural activities, despite being now in her seventies, but her grandchildren recall that she was very strict in her observance of the Sabbath, and never gardened on Sunday, "not even to pull one weed!" (39). After WWI, Emily admitted that the steep slope of Elmswell was beyond her declining abilities, and moved to her final garden back in Wanganui. She and Jessie established a vegetable garden, croquet lawn, and a flower garden, and Emily ended her days there at the age of ninety-seven, in 1936. Even in her final years she continued to be active in the garden and wrote to one of her grandsons: "I am glad you like gardening--it is the most wholesome occupation given, so what with tidiness and gardening I trust you will one day become a true man" (41). (Carman 40)

Kerry Carman's thorough introduction, accompanied by old photographs, provides an excellent context for the text of Emily's own writings which follow, pleasantly illustrated by Carman's paintings of the old-fashioned, native, and exotic flowers of Emily's gardens. Emily's writings could be mistaken for those of a true 'Suffolk lady,' as they are full of references to traditional English garden plants and practices; however, the references to NZ natives reveal her curiosity and eagerness to expand her plant repertoire by any means, echoing the craze for the exotic that gripped all of England's horticulture in Victorian and Edwardian times.

This book reinforces the image of NZ as a 'little England' for much of its history of European settlement. However, it is obvious that, from the beginning, settlers included NZ natives in their traditionally laid-out gardens.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home