Edwardian Garden Style

Resources:

"Early 20th century gardens" (Katherine Raine, in The History of the Garden in NZ, Ed. Matthew Bradbury; Viking, 1995)

"Towards a Modern Garden" (Paul Walker, in The History of the Garden in NZ, Ed. Matthew Bradbury; Viking, 1995)

Cultivating Myths: Fiction, Fact, and Fashion in Garden History (Helen Leach, Godwit, 2000)

New Zealand Town and Country Gardens (Julian Matthews and Gil Hanly, David Bateman, 1993).

The New Zealand garden in Edwardian times "mirrored the affluence and optimism of those 'golden years'" (Raine 113). New Zealand had progressed to nationhood, and was no longer simply a British colony. New Zealanders were beginning to develop a sense of national identity based on the riches of their adopted land. Nevertheless, they were still closely tied to the motherland, and the debates about garden style there had repercussions in the Southern Hemisphere. As Raine points out, "these long-ago British gardens are the source of much of the ideas of beauty we are still re-creating all over New Zealand" (Raine 114).

In England, the debate raged between the formalist and the naturalistic philosophies, and spilled into gardening from other fields of aesthetics, where the Arts and Crafts movement arose in rejection of the loss of uniqueness and beauty associated with the industrial revolution. Likewise in gardening, the formalists, led by Reginald Blomfield, maintained that the classical elements of form and line must be sustained for true beauty; in the other camp, William Robinson enthused about a naturalistic effect (although NZ anthropologist Helen Leach concludes from her intensive research that Robinson's wilderness was not, as is often believed, a return to native habitat; rather, Robinson believed in "placing plants of other countries, as hardy as our hardiest wild flowers, in places where they will flourish without further care or cost" 102). The working partnership of architect Edward Lutyens and artist-gardener Gertrude Jekyll helped to bring the two camps together, with Lutyens' geometric garden layouts softened by Jekyll's abundant plantings.

In New Zealand, some wealthy landowners scrapped their unpretentious cottage gardens in favour of the dictates of formalism. One garden in Dunedin, at the turn of the century, boasted "geometrical terracing and a grand river-rock staircase leading down through plantations of rhododendrons and other choice exotics, to a lawn, summerhouse and pool enclosed with tree ferns" (Raine 115). There were those, however, who heeded Robinson's call for naturalism.

Raine suggests that "one of the most profound changes in New Zealand gardenening in the early 1900's was the shift in approach towards a more natural disposition of features and a desire to conserve and enhance the character of the site" (119). David Tannock, then Supervisor of the Dunedin Botanic Garden, advised against many popular Victorian garden practices in his 1914 Manual of Gardening in New Zealand, including levelling and terracing the landscape, island beds cut into lawns, and parterres edged with box and filled with gravel, saying instead that "when deciding on the position of a new house due consideration should be given to all natural features, and no bush or tree of a suitable kind should be removed without a reason...banks and terraces are better formed into rock gardens...a hollow will provide a suitable site for a water or bog garden, and if there is a stream or creek some fine effects can be obtained" (in Raine 120).

Indeed, the relatively low cost and availability of land meant that middle class New Zealanders had large tracts to landscape, and many extensive gardens were carved out of cleared paddocks over the years. As on English estates, "no longer was the conventional middle-class garden simply green walls with a colourful carpet and specimen plant 'furnishings' dotted about. Under the influence of arts and crafts design, the spaces within the garden were subdivided and became more complex. Passageways and arches often linked a series of enclosures and led to garden buildings such as tea houses, arbours, and ferneries" (Raine 121). The flavour of pioneering New Zealand was, however, still observable in the rustic style of most garden structures: "fieldstone edgings for paths and raised beds; bridges, seats and arches made of rough branches; trellis fences, panels, and frames, and--the ultimate in vernacular building with materials at hand--whalebone pillars" (Raine 121).

The other factor affecting New Zealand gardens of this time was the increasing availability of plants from all over the world. New Zealanders enthusisatically adopted Jekyll's immense herbaceous borders, and, as Raine comments, "it could well be asserted that the real reason the border has gained in popularity as a garden feature here...is because so many New Zealanders continue to garden out of a true love of plants" (124). Emily Marshall-White, the "Suffolk lady" profiled in a previous posting, is a good example of a New Zealand gardener whose gardens throughout her lifetime show the slow change from Victorian formalism through a more naturalistic approach, and whose deep love of plants from all over the world sustained her gardening efforts into her nineties.

As the twentieth century limped through two World Wars, and into an age of modernism, New Zealander gardeners tended to remain traditional. Paul Walker, writing of the 1940's, comments that "even when Massey [an Auckland architect of the time] contrived his houses in an apparently modern style, his garden designs featured axial arrangements, raised or sunken areas with fountains and shrub and flower borders, pergolas, pavilions and stone-paved terraces that were derived from the traditions of Gertrude Jekyll and Edward Lutyens rather than anything contemporary" (155). Allegiance to England continued to be in evidence, in the 'coronation collection' and the 'crown jewel collection' offered by a Kiwi nursery in 1953, and in a series of articles run in the Home and Building magazine by Alfred Cole, 'the Royal Gardener.' Minor forays into modernism, such as the articles by Odo Strewe, an immigrant to New Zealand from Germany, and a modernist architect, were short-lived and largely ignored by the gardening public.

Two New Zealand gardens of Edwardian vintage that remain are both near Dunedin, in NZ's South Island. Larnach Castle's current gardens, although dating only from 1967, respect the castle's original formal garden layout from the castle's building date of 1871, including features such as a marble fountain from Pisa, a topiary knave and duchess from Alice in Wonderland, a petanque court, and a laburnum pergola.

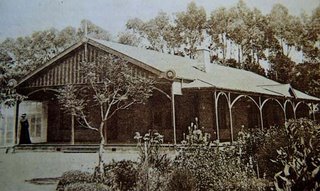

At the other end of the Edwardian spectrum, nearby Glenfalloch Woodland Gardens retain the layout and many original plantings dating from its 120 years of conservation efforts by successive owners.

(image from Glenfalloch Gardens website)

(image from Glenfalloch Gardens website)To this day, many well-respected New Zealand gardens still follow the tenets of the Edwardian style, and current issues of the popular New Zealand Gardener magazine regularly reference artist Gertrude Jekyll's lessons on colour harmonies.

One example of such a garden is that of Bev McConnell, the doyenne of Kiwi gardening circles (Bev and garden journalist Gordon Collier are co-judges of the New Zealand 'Gardens of Regional Significance' scheme). Bev's garden, 'Ayrlies' just south of Auckland, is a wonderland of beautiful garden features. It is regularly included in books about special New Zealand gardens, and one such, New Zealand Town and Country Gardens (Matthews & Hanly, 1993) describes it this way: "It's a tribute to Bev's gardening skills that the lakes, waterfalls, and woodlands at 'Ayrlies' look like naturally occurring features. She and Malcolm started in 1964 with an exposed, undulating paddock. The ups and downs of the land provided the opportunity for drama, with vistas from the high spots and intimate areas in the hollows, linked by curving steps and meandering paths which create a feeling of anticipation: what lovely surprise will be encountered around the next bend? The finishing touch is Bev's skillful plantings, tying the design together. She can be likened to a landscape painter, the garden her vast canvas..." (52). A present-day Gertrude Jekyll--the garden even boasts a set of Lutyens-style circular steps!

The McConnells have heeded Tannock's 1914 advice to make the most of the natural geography of the site, and applied Jekyll's colour theories artistically and imaginatively, while showing a lick of Kiwi ingenuity in the many and varied garden buildings. The following photos provide a glimpse into the Edwardian-style beauty of Ayrlies.

These gardens were to last longer than her second marriage, which ended after three years when Mr. White became frustrated with his inability to access Emily's familial wealth, due to the new Married Women's Property Act of 1882.

These gardens were to last longer than her second marriage, which ended after three years when Mr. White became frustrated with his inability to access Emily's familial wealth, due to the new Married Women's Property Act of 1882.

The garden surrounding Kemp House was established in 1822 by the Reverend Samuel Butler who lived here for ten years. The garden is "unique in that it has been in continuous cultivation for [now] 184 years and still reflects the balanced formality of the Georgian period" (19,

The garden surrounding Kemp House was established in 1822 by the Reverend Samuel Butler who lived here for ten years. The garden is "unique in that it has been in continuous cultivation for [now] 184 years and still reflects the balanced formality of the Georgian period" (19,